|

|

| ACTUEL magazine, 1982 |

By Michka Assayas and Thomas Johnson – Translated by Jaak Geerts

In 1982 a couple of French Journalists tried tracking Syd Barrett down for an interview. They called in at his last known residence in London, (the Chelsea Cloisters Apartments) to find the only thing left behind by Barrett was a bag of old laundry. The French magazine article in ACTUEL tells of their full story and meeting with Syd Barrett.

I managed to buy a copy of the Actuel magazine from Ebay a few months ago, but unfortunately my French was a little rusty. Parts of the article had been translated before, but never in FULL. Thankfully one of the ASTRAL PIPER members living in France, is brilliant at the French to English translation process, so now for the first time ever, the full article is available for everyone to read in English.

Although I certainly do not agree with some of the things said by this article on Syd Barrett, (and there are many incorrect details), I still feel this magazine article was extremely interesting, certainly more so than many of the re-hashed articles appearing frequently these days on the news shelf. Of particular interest is the association and mention of long time Barrett expert Bernard White.

A big "thank you" must go to Astral Piper member, Jaak Geerts from France for the time consuming translation. (And Brain Damage thanks Dion/Astral Piper website for the permission to use this on our site!)

|

ACTUEL magazine, 1982

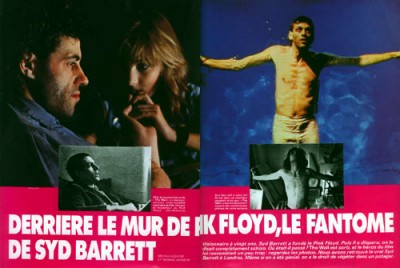

BEHIND THE WALL OF PINK FLOYD,

THE GHOST OF SYD BARRETT |

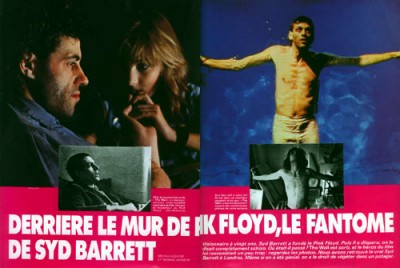

At the age of twenty, the visionary Syd Barrett founded The Pink Floyd. Then he disappeared, people saying he had turned completely schizophrenic. Where did he go? The Wall was released, and the hero of the film resembled him just a tad too much: just take a look at the pictures. We have found the real Syd Barrett in London. And even if a man has been a true genius, he still has the right to vegetate in a kitchen garden.

Phew! I really must look a sight, standing here in the middle of this Cambridge suburb street, with this bloomin’ laundry bag under my arm!

A pair of navy blue velvet trousers, some striped pyjamas, a pair of white socks and a blue pullover: these are the clothes Syd forgot in the London flat he lived in a month ago.

I had been trying to track Barrett down for several days when finally I was brought to a London estate agency. The girl cried out: “Mister Barrett? You mean the sick bloke? The one who locked himself up in his flat all day? He’s gone. He had some health problems; I think he went back to Cambridge to live with his mother.”

So the girl from the agency gave me the laundry bag. What an unexpected stroke of luck... Not one single journalist had managed to get close to Barrett since 1971, not a single picture had been taken of him. And all of a sudden, I am given the perfect excuse to meet him!

Now, here in Cambridge, I’m less happy with myself. I’m a bit ashamed of the stratagem, and I’m nervous when I think about meeting rock music’s great visionary, the founder of Pink Floyd, the man who left his mark on the band’s exceptional first album; Barrett who is said to be locked up, beyond the point of no return, inside schizophrenia. And now that I am confronted with this narrow street, these hundreds of perfectly identical houses, this caricature of Britain’s suburban cruelty, I feel heavy-hearted.

I enter a chemist’s shop to ask my way.

“First street to your right, Sir." Do you know Mrs. Barrett? "Yes, of course, she comes here often to buy medication for her poor son. He has a nervous problem, you know. I think he’s taken too many drugs. It’s horrible, you know."

Does he go outside from time to time? "Oh yes, he often does. He goes shopping for his mother. He’s a very nice person, but he hasn’t always been that way. Nowadays, everybody likes him around here.”

Half past four. I’m in front of the Barrett house, and I’m not the only one there. There’s a young hippie who paces up and down in front of the house, a bottle of milk in his hand, kind of a weird look in his eyes. He glances stealthily, hesitates. His hero is there and he doesn’t know how to go near him.

I ring the door bell.

Syd Barrett...who remembers him? Apparently, Pink Floyd’s leader, Roger Waters does. He has just conceived a trying metaphysical play in the form of the film The Wall, inspired by the eponymous double concept album.

A guy called Pink, who plays in a successful rock band, is depressed after an American tour and, more generally speaking, with the pangs of life itself. To cap it all, his wife cheats on him with a peace activist. When he becomes a prey to a raging metaphysical crisis, Pink loses his self-control, destroys his furniture, shaves off all his hair, has apocalyptic visions, thinks he’s Adolf Hitler and ends up being completely obsessed with the idea of building a wall. In short, Pink goes mad.

This pathetic character is a paranoid projection conjured up by Roger Waters, Pink Floyd’s “mastermind” and a man who suffers from acute misanthropy. But it’s also, by means of very precise details, the story of Syd Barrett, the founder of the band.

A visionary genius at twenty, labelled schizophrenic at twenty-two, perhaps for the rest of his life. Rock history is paved with dazzling, tragic destinies like this one: Peter Green, Fleetwood Mac’s prodigious guitarist, went on to become a gravedigger for several years; Roky Erickson, whom no one dares to approach anymore; or Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys’ sublime composer, who has practically sunk into his second childhood. Not to mention the long-term depressions of Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, or the suicides, e.g. Ian Curtis of Joy Division, the most mythicized of them all. Let alone all those Romantic junkies...

Syd Barrett remains the most enigmatic of all of rock music’s shooting stars. There is a hazy shade of mystery and rumours that clouds his life’s story. His influence regularly manifests itself where one would least expect it. During the Sex Pistols’ early days, Malcolm McLaren wanted to turn them into a psychedelic band covering Syd Barrett’s songs.

English rock never really got over Barrett’s sudden disappearing act. American psychedelia – acid rock – was actually basic rhythm’n’blues, only louder and more insane. The early Pink Floyd made British psychedelia slide much further, somewhere between 2001 A Space Oddity and Lewis Carroll, into greater emotional audacity, more caustic musical forms and agonizing patterns of tenderness. This was the time when people did everything they possibly could in order to delve into their own depths. Bob Dylan, hallucinating, moved some puppets around in a completely schizoid manner during a press conference. People dropped acid so as to blow up all boundaries, draw creative energy from madness, build bridges between painting, rock music, architecture, cinema and poetry.

First of all, we tried to make contact through professional channels. But Syd Barrett doesn’t have any record company, manager or publishing company anymore. So I called Bryan Morrison, his former manager.

“I have nothing to say to you." You mean you’ve lost all contact with him? You’re not interested anymore? "That’s right.”

A couple more phone calls, all to no avail. There have been several rumours circulating for the past ten years. Syd’s in a mental hospital. Not at all! He lives all alone on the top floor of the Hilton Hotel in London, in a suite the band has offered him for the rest of his life. No, no, that’s not it either – he resides with his mother in Cambridge, never leaving the house, living in the cellar where he grows mushrooms...

I guess we’re lucky, just before we’re off to London, a bit blindly really, there is a short notice in the New Musical Express: ‘Terrapin’, the fanzine once published by the “Syd Barrett Appreciation Society”, has been reissued.

Bernard White, the fanzine’s editor, tells us over the phone in a poised and solemn voice: “I don’t want to get involved in anything before I know who you are. You must understand that the press has spoken badly of him too often in the past, and I want to know what your intentions are.” We accept the test.

White lives all by himself in Hampstead, the north London “artistic” and peaceful neighbourhood, in a tiny maid’s room. Its walls are covered with psychedelic posters, all collector’s items, and on a rickety chest of drawers stands an immense wooden chest, covered in some kind of Indian cloth, in which White keeps all the fanzines he photocopies at his own expense, and all kinds of documents concerning Syd Barrett. White never parts with the key to his chest. Mounted under glass is one of the earliest pictures of The Pink Floyd, with a ruffled looking Barrett amongst them, a modern day Rimbaud of sorts. It’s pretty obvious that we are in a sanctuary.

White, somewhere about thirty years old, is a strange creature. He’s short, sickly, his hair cropped like a cosmonaut’s, he has a sweaty handshake and is dreadfully awkward and shy. He has devoted his life to Syd Barrett for ten years now. In civilian life, he is an unemployed record shop employee.

He informs us solemnly: “You’ll have to present this man as an artist.” This will be his leitmotiv throughout. Clearly alarmed by the lies and obscenities that have been printed on Barrett – e.g. he eats grass and tops his head with cream - White tries to justify himself: “I try to protect him.”

He shows us his most precious items: a promotional film for “Scarecrow”, one of the Floyd’s earliest songs, copied onto a VHS cassette. And even rarer: another film that looks like it dates back to the brothers Lumière era, shot in super-8 by a friend of Barrett’s at Cambridge when he was seventeen. Then it’s time to listen to three previously unreleased songs, “Opel”, “Birdy Hop” and “Word Song”.

The contemplative meeting reaches its highest point. White brings out two huge binders filled with press clippings.

“I’m the most important authority on the subject of Syd Barrett”, White explains. “I can understand him. Just like him, I have been called a madman. I spent one year in a psychiatric hospital, and six years locked up in this room.” An eerie feeling takes hold of the sanctuary. We imagine White all on his own, on a winter’s night, staring into the void, listening over and over again to Barrett’s tortured voice reciting his fragile and impassive poems one after the other.

Finally, White produces a rough picture, drawn in colour pencil with sinewy lines all over it, just like a bunch of naïve approximations of geometrical patterns. The picture is signed Roger Barrett 1979. Roger Barrett is Syd’s real name. And White informs us that that’s how Barrett wants to be called nowadays.

Where did White get this drawing? What does he know about Barrett from 1972 until now? White refuses to reply. If we want to gain access to Barrett Wisdom, we have to be “prepared” and follow some kind of initiatory path. He prefers to show us his weekly mail: some thirty odd letters, in which people eagerly lay claim to information concerning Syd Barrett.

He has never ceased to be worshipped. Around 1974, so the story goes, everybody wants to resuscitate Barrett. Jimmy Page gets someone to look into the case. David Bowie, who has just covered “See Emily Play” on an album, tries to get him back into the studio. Eno has the same idea. It’s all in vain.

And now there are all these letters, practically all of them written by very young people, from all over England.

It’s 1966. Londoners passionately indulge in psychedelia, imported from San Francisco, and ingest huge quantities of LSD. The three other members of Pink Floyd, Roger Waters, Nick Mason and Rick Wright, met a year before when they were studying at the same school of architecture on Regent Street. Barrett came to London from Cambridge to study painting in an art-school. He is nineteen years old and apparently is much more drawn to the trinity of ‘sex and drugs and rock’n’roll’ than his three partners, of whom he initially says they are “not really very exciting people”. Of course, Barrett is the first of the quartet to drop acid.

The first genuine concerts of The Pink Floyd take place early 1966, during some highly experimental parties. On these nights, eccentric musicians, poets or just plain nutters take to the stage one after the other – the term “performances” is already used.

Nick Kent, a rock journalist, remembers a Pink Floyd gig near the end of 1966, before their first record was released.

“They had no qualification whatsoever, but they had one thing going for them: they were hip. They played, just like every other band did at the time, classic rhythm’n’blues songs, like ‘Louie Louie’ and ‘Road Runner’. But they had read some stuff about the West Coast and psychedelia. So instead of playing these songs in two minute versions, they made them last ten minutes... complete improvisation, dissonant and inventive.”

That’s when destiny rears its head in the form of Peter Jenner and Andrew King. Jenner is a professor in sociology and King is a cybernetics engineer on the dole. They’ve started an independent company and are eager to get the underground sounds out. They know strictly nothing about rock music, but their instinct made them track down the band of the century, so as to enable them to make a fortune.

Their initial choice was The Velvet Underground, but Andy Warhol beat them to it. What follows is a burlesque situation: Jenner heads off to meet the members of The Pink Floyd and explains to them that they “could become bigger than the Beatles”; they are amused, but in a sceptical way. Waters, Mason and Wright consider The Pink Floyd as some sort of hobby, whereas Barrett takes his music very serious. Jenner takes him aside and says: “Why don’t you start writing songs?”

So Syd starts writing, just when the band thinks about splitting up: Waters and the two other band members attend to their architecture studies. This is the era when The Beatles and The Stones digress “artistically” for the first time, with Revolver and Between The Buttons respectively. On the West Coast, two of psychedelic rock’s masterpieces are released: 5th Dimension by The Byrds and Love’s first album. Barrett listens to these four albums continually.

The songs Barrett writes, the ones the band will record a couple of months later, are very much linked to the themes that are in at that time: mysticism, the I-Ching, science fiction and the extremely British fantasy world of Tolkien, elves, gnomes and magicians.

Early 1967, Pink Floyd means big business. The national press discovers underground culture and things get rolling. The band signs a recording deal, heads off on a tour across the country, releases a 45, records an album and tours America: a whirlwind that lasts six months, a pure frenzy during which something happens to Syd Barrett.

In June 1967, the band makes a television appearance to promote “See Emily Play”, their first hit record. Barrett wears a pop star’s outfit: a satin shirt and a pair of flowery trousers. For the second show, he hasn’t shaved and wears creased clothes. For the third show, he shows up in a princely outfit, but when it’s time to go on, he changes into a set of rags.

In October, when they’re touring the States, Barrett refuses to lip-sync when they appear on a television show. During an interview on the “Pat Boone Show”, he remains mute and stares at the show’s host as if he sees through him. The manager prefers to cancel the rest of the tour instead of taking the risk of being confronted with a suicide.

The downfall sets in.

Everyone who was there at the time agrees: something awkward, almost tangible, appears in the look in Barrett’s eyes. Joe Boyd, who produced their first 45, and who hasn’t seen the band in a couple of months, notices it practically straightaway: “If there was one thing that had struck me about Syd, it was the glimmer of mischievousness he had in his eyes. When I saw him again, it had completely disappeared. It was as if someone had drawn the blinds. Nobody home.”

Nick Kent recalls one of the last gigs the Floyd did with Syd Barrett: “It was clear that the band couldn’t function anymore. Barrett remained isolated at the back of the stage; he didn’t tune his guitar at all. He looked fabulous, though: his long hair, his ghostly face with black eyeliner around the eyes... On this enormous stage, he seemed physically cut off from the rest of the band... There was one roadie who was solely in charge of switching off the sound of his guitar when he lost control.”

Nick Kent knows better than anyone else what happened next. In 1974, he conducted the first in-depth inquiry into the Barrett case. Illustrating his article in the New Musical Express was a huge picture of the artist aged nineteen, the word “cancelled” stamped over it.

Kent, it has to be said, is a real case himself. A legendary critic whose existentialist devotion to rock’n’roll and devastating sense of humour have been copied a thousand times, without ever being equalled. Nick Kent is the first rock journalist to have signed autographs. A tall and spindly person with a reptilian look about him, dressed in his typical and inimitable hobo-like chic, Kent talks about Barrett as if he were one of his personal obsessions. We retreat into the minuscule listening booth he has at his disposal in the office of his magazine and Kent launches into a monologue that will last over an hour, hypnotized by his subject, staring into space.

“When I was working on my article, I heard at least three hundred stories about Syd Barrett. The most widely spread was the one of him living with a couple, ‘Mad Jock and Mad Sue’, who put acid in his coffee every morning. That way, he is supposed to have been on one long trip for two or three months without even being aware of it.”

After he’d been sacked from the Floyd, Barrett throws one final message in a bottle into the ocean: he puts out two erratic, unsettling solo records, on which he can be heard fighting against his own demons with wavering energy, his voice raving and frightened. These are two underground classics, two gems that some start nagging about to the members of Pink Floyd.

There is even a mythical third album. Peter Jenner, the Floyd’s former manager, was present at the recording sessions late 1974 or early 1975.

“It was a distressing experience, because something was still present inside him, but I was under the impression he didn’t want to bring together all the pieces of that ‘something’. During takes, he would just go out and vanish. The sound engineer used to say to me: ‘If he goes out and turns to the right, he’ll be back; if he turns left, we’re not going to see him again for the rest of the day.’ He never got it wrong.”

Recordings do exist, and it goes without saying Bernard White has them in his possession. They are unstructured guitar solos who were meant to be the basis of songs Barrett has never sung. Apparently, he did write some lyrics to them, though. He is said to have had a song lyric typed out on a typewriter and handed over to him, after which he imagined someone was going to make him pay for it. Things never went any further.

A couple of years prior to that, Syd Barrett had shared a flat with a painter by the name of Duggie Fields. Syd’s room can be seen on the cover of The Madcap Laughs, his first album, the parquet painted in orange and blue, with a bedazzled Syd in the foreground, eyes black with eyeliner, a naked woman’s back pictured in the background...

Let’s go and talk to Duggie Fields. The painter still lives in the same flat, in Earl’s Court, one of London’s fancy neighbourhoods. The decoration is not the same anymore: huge paintings with contrasting colours cover the walls. Everything is clean, beginning with Duggie himself. He is dressed in red satin, has his hair combed back, a little curl dangling down his front. Syd Barrett is long gone. Duggie describes what Syd’s room looked like in those days:

“There was a mattress on the floor, a dirty carpet, some pictures he was painting, a record player and some records – his own and some blues - a guitar, the i-Ching and a wire-and-paper structure hanging from the ceiling. That was it.

“He had painted the parquet without cleaning it or moving the furniture. Fag ends, matches, dog hair... it all got stuck into the paint. The windows, covered in hessian, couldn’t be opened anymore. There was a stench in the room that was unbearable. As soon as he went out, I’d take advantage of the occasion to clean up, but he hardly ever went out."

What did he do all day? "He could stay in bed for days on end, without getting up. And nobody was able to anticipate when he would finally get up.”

The flat was swarming with people. Mandrax and LSD were being dealt. Quite a number of young girls would try and chat up Syd, they would stay in front of his door for hours, drumming with their fingers, sobbing away... they literally had to be thrown out.

“He had a girlfriend, but it didn’t work out. One day, he opened the door and threw her into the other room, like he would have done with an old bag, without a word. I had to part them more and more often.”

There was only one way to gain access to his room: get him a supply of Mandrax, one of the few things that he was still interested in.

“I would always check up on things after he had been in the kitchen. Once, the corridor was filled with smoke. He’d fried some chips, and then when the oil had completely evaporated, the pan had melted and the curtains had caught fire. Syd had put out the fire and had calmly returned to his room, without saying anything.”

“He had an old Cadillac with a sun roof, and one day, he just gave it away to some guy he met in the street... a perfect stranger. Sometimes, I would find him covered in blood. He had smashed the door to a cupboard in the kitchen because he hadn’t been able to open it.”

In the end, Duggie can’t take it any longer and moves out.

Syd invites two other people to come stay with him. Then he has a sudden change of heart: he decides he wants to go back to his family, talks about taking care of his health again, about getting married to his girlfriend, becoming a doctor...

The girl follows him, but doesn’t stay around for a long time: she’ll soon get sick and tired of the blows.

One day, when his mother comes home, she finds the whole place devastated. Syd has smashed all the furniture, the television set and the dishes to pieces. He’s lying on the floor, not moving. Shortly afterwards, the ambulance arrives. He’ll spend several years in a psychiatric hospital.

So what goes on these days? Nothing has seeped through for a number of years now. And now I’m disclosing part of the secret thanks to this strange and derisory magic key: a laundry bag.

The estate agency doesn’t know where he lives, but they’ve given us his sister’s telephone number. I ask her how he’s doing. “Yes, he has been very ill. He had a stomach operation. Besides, he is still ‘sick in his mind’." But what does he do nowadays? "Oh, nothing much. He lives a bit of a solitary life, with my mother. You know, he’s very sick. I think it’s innate. It’s all over for him." But this must be hard on your mother! "Yes, it’s a real strain on her, especially given her advanced age. But she’s a mother. He lives a peaceful life now, and he doesn’t want to see anybody. He doesn’t even recognize his friends from London. You know, the time he spent in London didn’t do him a lot of good. I think he’s as happy as he possibly can be now.”

|

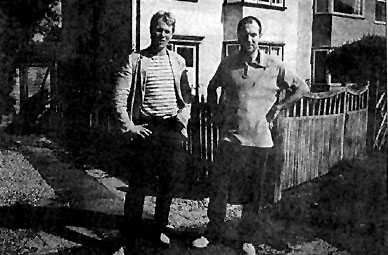

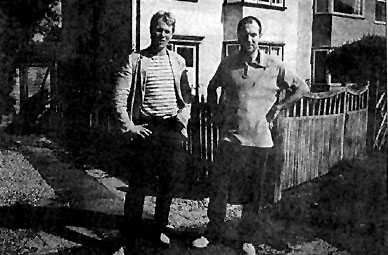

| Roger Barrett (right) and Actuel journalist |

And so I finally stand in front of this Cambridge house, trying not to blush too much while waiting for someone to answer the door.

No reply. I ring again and push the door open. In the small garden, an old lady is cutting the rose-bushes. A shadow appears at the end of the corridor and moves slowly towards me.

“Hello!” We’re equally surprised, our voices coincide.

“I brought you this. I think it’s your laundry".

"Oh, yes! From Chelsea! Yes...”

He’s a tired and older man. His hair is very short, going a bit bald at the temples. His features are haggard, his look is glazed, and his arms are dangling. He is thin and his skin is flabby. His mother didn’t hear me arrive and stays in the back of the garden. From time to time, he looks at her, stealthily.

I’ve been trying to contact you; I went up to Chelsea, so they told me they had this bag of laundry for you, and that you were living with your mother. "Thank you very much! Do I owe you something? Did they make you pay for anything?" No, no, it’s ok! What are you up to these days? Do you paint? "No... I had an operation recently, but it’s nothing really serious. I’ve been meaning to go back there. But I’ll have to wait. There is a train strike at the moment."

But that ended a couple of weeks ago already... "Ah, ok! Thank you..." What do you do in your London apartment? Do you play guitar? "No... no, I watch television, that’s all..." Don’t you feel like playing anymore? "No. Not really. I don’t really have the time to do a lot of things. I’ll have to find an apartment in London. But it’s not easy. I’ll have to wait...”

From time to time, he looks at his laundry and fiddles around with it. He smiles.

“I didn’t think I was going to get these things back. And I know I couldn’t write. I couldn’t bring myself to go and fetch them... Take the train and all that... But, yeah... I didn’t even write them... Mum told me she’d call them from the office... Thank you anyway...”

He is constantly trying to put an end to the conversation. He never stops glancing in the direction of the garden, where his mother is.

Do you remember Duggie? "Eh... Yes... I never saw him again... I didn’t visit anyone in London." All of your friends say hello. "Ah... Thanks... That’s nice...”

He speaks and reacts exactly like all the other people I’ve known that were undergoing psychiatric treatment. Waiting seems to have become his primary occupation, and the television helps to see time pass by.

Can I take a picture of you? "Yes, of course.” He smiles, tenses up, and buttons up his collar. “Ok, that’s enough! This is distressing for me... Thank you.” He looks at the tree in front of the house. I don’t know what to say anymore. That’s a beautiful tree. "Yes, but not any longer.. They cut it a little while ago... I used to like it...”

From the house, his mother’s voice is heard: “Roger! Come and have a cup of tea and say hello to my friends!” Roger Barrett looks back at me, in a start: “Ok... Well... Perhaps we’ll meet again in London... Bye..." "Yes, see you soon... Bye...”

When I leave, I come across the mad hippie again. He is leaning against a wall in front of the house, hiding behind a newspaper. I feel unbelievably drained.

There you are. That’s it.

But where can I find an explanation, or a justification for such a waste? What has happened in this crushed existence?

Theories abound.

Someone mentions a certain Ozzie, a fan who went to see Barrett six months ago to offer him a picture that represented him. She promises to write something down, and she keeps her promise.

“No way Syd Barrett is a lunatic. I don’t even go for the theory about him being schizophrenic. I’m sure that he has every control over his mind and uses it at will. He’s certainly unlike everyone else I’ve met up till now, but there is nothing insane, zombie- or acid casualty-like about him. He’s just taking a rest from mankind, a species he obviously deems useless and that he looks upon from an entirely different spiritual level. It’s hard to tell whether he is happy or not, but I’m pretty sure that he has organized his world as he intended, that he has excluded all the rest and lives inside his mind.”

According to White, the fanzine editor, “he could have become a guru and people would come to see him from all over the world.” Sure. But why didn’t he aspire to that? Why didn’t he aspire to anything at all? Barrett refrained from having a career and becoming a pop star. In spite of that, for several years, every time he mentioned Pink Floyd, he referred to them as “his band”. In a way, Barrett locked himself up in a state of indecisiveness and became a paralytic of determination. Why?

Everyone who knew him at the time agrees: in Cambridge, Syd Barrett was a cheerful, brilliant, extrovert young man. Storm Thorgerson, nowadays in charge of Hipgnosis, the graphics design agency that’s specialized in the design of record sleeves, was his best friend back then. Here’s how he sees it:

“People made Syd into the centrepiece of a cult that went way beyond his control. He went on a trip inside himself and ventured into musical explorations the other band members were unable to follow. After Richmond (the acid-spiked coffee), he wasn’t the same man anymore. But all of that would not have occurred had there not been some kind of predisposition... Syd had no discipline whatsoever. He had lost his father at a very early age, and he was way too mothered.”

When he was nineteen years old, like so many of the Cambridge friends he hung out with, Barrett got passionately interested in Indian mysticism. He tried to become a disciple of a guru who was originally from the north of India and taught the mysterious teachings of “Sant Saji”. His application was not withheld because the guru considered him to be too young. Storm Thorgerson: “It was another father figure turning his back on him.”

Roger Barrett was the youngest child in a family of eight. Nick Kent: “His mother always considered her son to be a genius. She made him live in an imaginary world. Dave Gilmour, of Pink Floyd, thinks it all started there. Needless to say, Mrs Barrett has always refused to accept the fact that her son wasn’t a normal person.”

So this would rather be a case of slow erosion than chain reaction. The origin of which would be, so to speak, a manufacturing defect. And the brutality of Pink Floyd’s success, together with all the excesses of that era, would finally get the better of a fragile structure.

“There are people who walked down acid lane and managed to pull through”, says Kent.

What is most fascinating about Syd Barrett is the fact that he succeeded himself in diagnosing the catalepsy that got hold of him. The lyrics to ‘Jugband Blues’, the only song on Pink Floyd’s second album (A Saucerful Of Secrets) that bears his signature, a song the band included as a charitable favour, already echo from beyond the grave:

“It’s awfully considerate of you to think of me here. And I’m much obliged to you for making it clear that I’m not here. And I’m wondering who could be writing this song.”

His two solo albums are two impassive accounts, delivered by a man who precisely wants to “make it clear that he’s not here” anymore. “When Barrett lived in the cellar at his mother’s place in Cambridge, he had an aquarium. And the records strike me in pretty much the same way: there’s nothing emotional about them. It floats and it’s extremely lunatic. There is something very English about it all. Like Lewis Carroll.”

Barrett is an English myth, as serious as he is frivolous – the England of nonsense and all those extravagant little clubs. The exact counterpart to the French romantic madman, morbid, arms riddled with holes, a victim of his own disorganised genius.

Even Bernard White, for all his mystic awe and respect, recognizes there is a certain degree of humour in the character. And even if the story of Barrett’s life is sad, it is by no means dark or sinister. One has to admit there is a certain amount of choice in his itinerary.

Nick Kent remembers: “When I was investigating the Barrett case, it reminded me of ‘Chinatown’. It’s a classic theme Dashiell Hammett used: the ‘gumshoe’, the private detective who wants to get to the bottom of things. He ends up being so obsessed with the whole thing, it all blows up in his own face. You try to understand what goes on inside a man’s mind – you try and approach in a logical way things that are completely devoid of all logic.”

There remains one man to be questioned. Who never knew Syd Barrett? An off chance, an intuition. Ronald Laing, the tortured ‘anti-psychiatry’ prophet, who does not consider lunacy to be a ‘mental illness’, but rather an inward journey, during which a person tries to find himself. A journey made necessary by the absurdity and the masked violence that can be present in a family. A journey that is cut off by the psychiatric treatments and thus becomes a never-ending series of wanderings. Laing’s lyrical and painful books were written at the same time psychedelia triumphed. And today, Laing has also disappeared...

On the phone, a voice, his secretary or his wife:

“No, Mr Laing does not speak to journalists. What you can do is make an appointment and pay, like any other patient, twenty-five pounds for a visit of half an hour. That’s the way it goes.”

A young, barefoot lady leads me into his practice and leaves me there by myself.

Laing enters. He huddles up in an armchair and his eyes avoid mine. I tell him Barrett’s story. He dozes off in his armchair, closing his eyes. Then, slowly, he starts mumbling something with a Scottish accent, which makes it hardly possible for me to understand him.

“I... I... I think I met him once or twice at some parties, at the time. He reminds me of Artaud, Rimbaud, Marcuse, Nietzsche, people heading towards thirty with all that passion and vision and genius and spark of theirs. And then there’s Mayakovsky, who killed himself, leaving a suicide note which read: ‘The love boat has crashed against the everyday.’ You feel programmed, conditioned, automated, and then you take some acid and all of a sudden, you discover Shiva’s dance and lots of other things in the same vein... But there is nothing that can help the visionary express his vision. People buy what he produces and think of him as some kind of merchandise. He thinks he can find love and understanding, that’s all. Then the songs seem to be getting emptier all the time. And everything becomes nothingness.”

Laing talks as if he’s been through it all himself. “In the end, there is no more energy left. And the visionary ends up resembling a washed-out floorcloth. The only thing he can do is sit down and do nothing. Or get on stage and play one single note. But that means nothing at all. The one who hears it, the listener, thinks of that note as nothing more than just noise, a ‘ploop’ played on a guitar chord.” Laing sinks deeper into his armchair, into his past, into his ancient concepts. Then suddenly, he ends the monotony. “Everything becomes ugly, uglier and uglier, ugly. Then, the person turns to other ways of thinking, alternative realities, suicide puts on another face. It’s only a breathing pause, a start: ‘I’m tired of it all, I’m off, thanks!’ A lot of people of his generation just said: ‘That’s it, bye!’ Or: ‘Do you want to see my body? Here it is.’”

Then, after a long silence: “How old is he now?" Thirty-six. "Well! You never know. He might have another stroke of genius.” I show him the photographs. He looks at them closely. "He must be on some kind of treatment. It’s... a sad story. You never know. After all, he hasn’t been tortured or physically damaged. He’s still in one piece. That might give him some hope again. But there is nothing we can do for him... not anymore.”

That same evening, at the Notre-Dame, a London club, we’re supposed to meet Dave Gilmour, Syd’s replacement in Pink Floyd. He goes there every Thursday to listen to some sixties records. Gilmour sits in a corner of the room with some friends. They all look old, or perhaps old-fashioned rather...

“Syd Barrett? I don’t have the time to talk about him. Your article has to be the last one about him. It’s not Romantic. It’s a sad story. Now it’s over.”

|

Interviews

Interviews  Syd Barrett interviews

Syd Barrett interviews  1982 - Actuel Magazine

1982 - Actuel Magazine